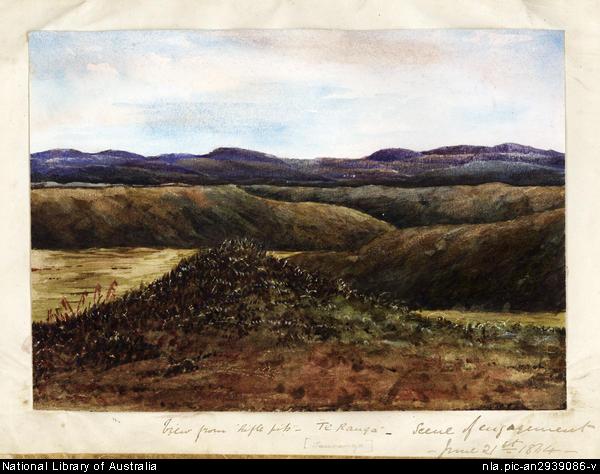

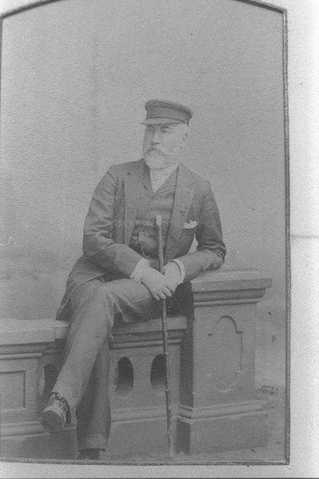

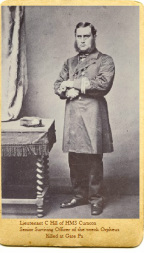

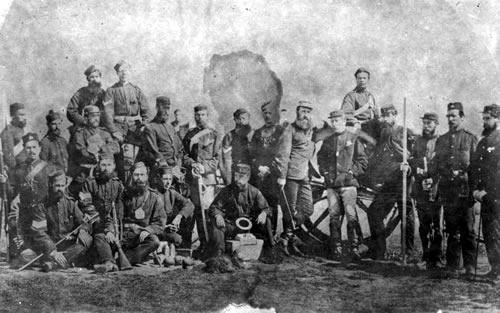

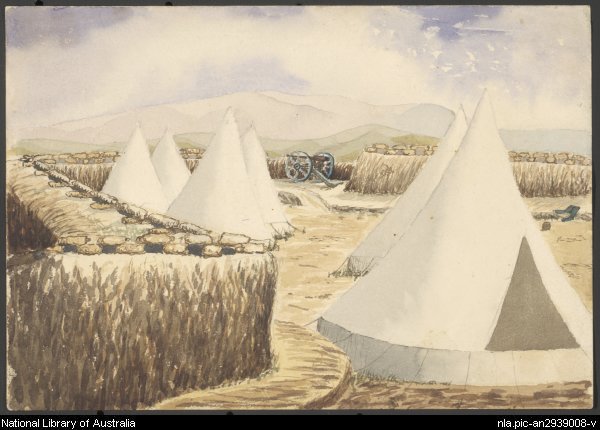

The next morning Colonel Greer marched a large contingent out of the camp at 8am. 3 Field officers, 9 captains, 14 subalterns, 24 sergeants, 13 buglers and 531 rank and file were under his command. In his report later that day Greer gave his account of what took place:

'I found a large force of Maori (about 600) entrenching themselves about four miles beyond Pukehinahina. They had made a single line of rifle pits of the usual form, across the road, in a position exactly similar to Pukehinahina, the commencement of a formidable pa. Having driven in some skirmishers they had thrown out, I extended the 43rd and a portion of the 68th in their front and on the flanks as far as practicable, and kept up a sharp fire for about two hours, while I sent back for reinforcements... As soon as they were sufficiently near to support, I sounded the advance, when the 43rd, 68th, and 1st Waikato Militia charged, and carried the rifle pits in the most dashing manner, under a tremendous fire, but which for the most part was too high. For a few minutes the Maoris fought desperately, and then were utterly routed.'

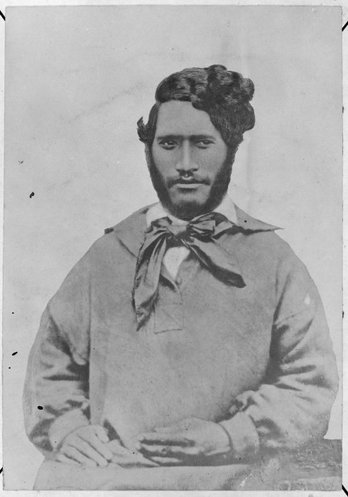

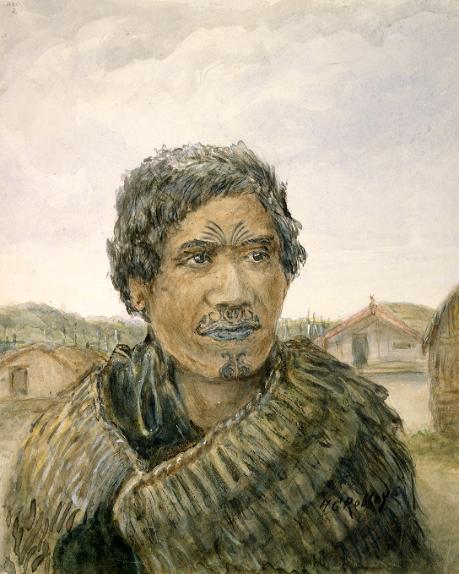

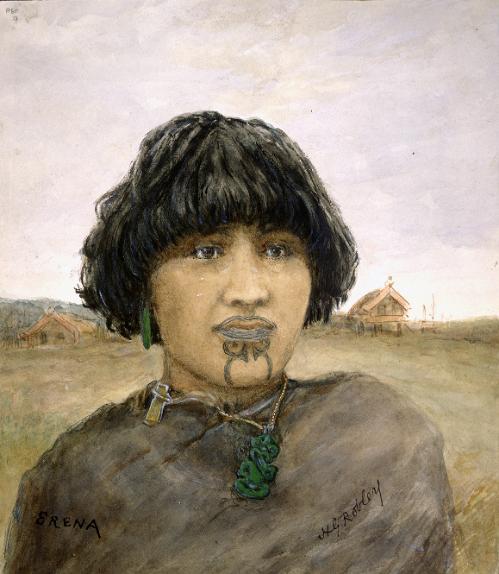

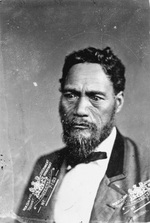

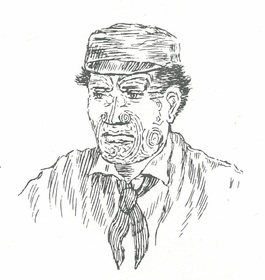

The Māori party, led by Rawiri Puhirake, did not retreat but stood their ground. Reinforcements also came to their support, but too late. The steep ravines surrounding the ridge made for difficult pursuit.

Events marking the 150th anniversary are taking place over the next 2-3 days, including a memorial service on the site of the battle.

Col H H Greer to Deputy Quartermaster-General, 21 June 1864, Enclosure in No.19, Further Papers Relative to the Affairs of New Zealand, Great Britain Parliamentary Papers, 1865, Vol.XXXVII.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed